Luxury apartments to open soon in former AT&T building

Mickey Shuey, Indianapolis Business Journal

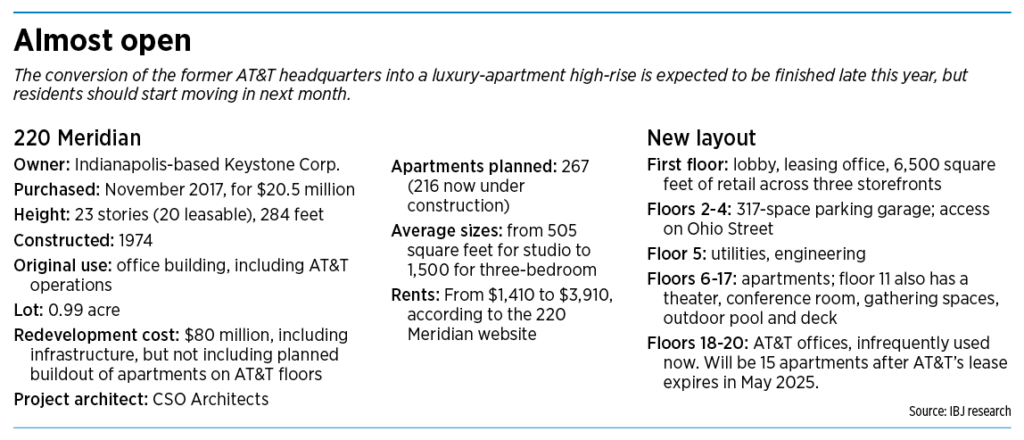

A local developer’s $80 million conversion of a 20-story office building into luxury apartments is the largest project of its kind downtown.

But experts say it could be a blueprint for other firms seeking to turn increasing amounts of unused office space into apartments and condos.

Keystone Corp. has been working on its overhaul of the tower at 220 N. Meridian St. since 2018—well before COVID-19 changed the way companies think about offices. The project will create more than 260 high-end apartments just a block north of Monument Circle.

Built in 1974 for AT&T predecessor Indiana Bell Co. what’s now called 220 Meridian has a brand-new three-story parking garage within the original footprint, a new front entrance and completely reengineered infrastructure and utilities for the apartments and for AT&T, which is—for now—maintaining offices on the top three floors.

And despite delays tied to both the building’s complexities and the pandemic, the project is nearing its end. Dozens of units have been pre-leased (Keystone declined to say precisely how many) and move-ins are set to start by the end of April.

“These are challenging, complicated projects, and not a lot of people are taking this [type of development] on because of the challenge,” said Jennifer Pavlik, Keystone’s chief of staff. “But at the end of the day—to us—this is exciting, because we have an opportunity to do a transformational development project in downtown Indianapolis that brings opportunities and people downtown.”

The city contributed $16.7 million to the 220 Meridian project as well as Keystone’s planned redevelopment of the Illinois Building at Market and Illinois streets into The InterContinental hotel, a project that has been delayed. The city will pay off the project’s bonds using revenue from a downtown tax-increment-financing district.

That financing means 220 Meridian must offer at least 43 units to individuals earning up to 80% of the area’s median income at subsidized rents. However, the units will not differ from the other studios, one-, two- and three-bedroom apartments that will be offered at market-rate rents.

According to the 220 Meridian website, a studio apartment will start at $1,410 a month. The most expensive apartment—a three-bedroom, three-bath in 1,561 square feet—is listed at $3,910 per month.

Infrastructure challenges

Keystone acquired the 220 Meridian property in 2017 for about $20 million, from Cleveland-based Geis Properties. As part of the deal, AT&T was allowed to retain 75,000 square feet on the top three floors through at least May 2025, to subsidize its office operations in a neighboring building. But other than AT&T, the building had been largely vacant since about 2009.

Keystone initially considered leaving the sixth through 10th floors as office space, but the firm ultimately opted for a complete conversion to apartments. Initial plans called for 131,000 square feet of office space and 160 apartments, including 32 below market-rate.

Such adaptive reuse projects are among the most complicated, said Isaac Bamgbose, principal of Indianapolis-based New City Development LLC, who isn’t involved in the Keystone project. That’s because developers are forced to use much of the existing bones of a property, while still modernizing the infrastructure.

Bamgbose oversaw the early stages of the Bottleworks District project, an ongoing $300 million development that included an adaptive reuse of the former Coca-Cola bottling plant along Massachusetts Avenue.

“Everything is complicated with adaptive reuse, especially when you’re switching from one use to something completely different—here, from office to residential,” he said. “It just begins to become pretty complex pretty fast.”

Keystone officials said ensuring that the process was done properly has proven to be highly complicated and drawn-out. It didn’t help that AT&T maintained operations on the building’s top floors throughout construction (although at reduced capacity due to the pandemic).

“The challenge was juggling the existing tenant, juggling the new infrastructure for the apartments, and then incorporating existing infrastructure as well,” said Mark Tomyn, Keystone’s vice president of development and asset management.

Tomyn said among the many challenges tied to the building’s mechanical, engineering and plumbing operations, four stood out.

The first was modifying the building’s electricity substations and installing new transformers to give each apartment its own electricity meter for utility billing.

The second was providing fresh air to the entire building through a recirculation system. He said the new dedicated outdoor air system, which is part of the fifth-floor mechanical components, required new vents and air shafts throughout the building. The developer also opted to ensure each unit had a few windows that open about 4 inches, to allow for additional fresh air.

Third, Keystone had to find a way to maneuver each unit’s clothes dryer vent in a way that didn’t encumber the office levels.

“We have an existing tenant—I don’t want to make Swiss cheese of their floor,” Tomyn said. “We had to redirect [the vent] to the core of the building, then get the core shafts to go up to the roof. We wanted to do it right … [because], once you start going up, by code, you have to go perfectly straight up—you can’t deviate at all.”

Last, the development team had to install three massive, 650-ton chillers to provide cooling to the entire building.

Other complexities abounded on the project, as well, Tomyn said.

Keystone designed the building to allow AT&T a dedicated elevator separate from the bank of elevators by the lobby, and it spent more than a year building the parking garage on the second through fourth levels. The property will soon have a new pool, too.

Further complicating the situation, Tomyn said, is that all the new systems must work seamlessly with the existing infrastructure that is still in use, such as baseboard heating on the upper levels, but will ultimately be transitioned once AT&T makes its exit.

“All of it’s about the infrastructure—I [had] to keep all the old stuff to take care of AT&T and had to create and use all-new infrastructure for the units, which is totally unique from the office side,” he said.

Something different

Adaptive-reuse developments aren’t unusual in central Indiana and especially not in downtown Indianapolis, but conversions of 20-story office buildings are rare. In fact, IBJ research found that the 220 Meridian project is perhaps the first of its kind, at such a large scale, in the city’s history.

“Most other office buildings [that have been converted] are older ones with smaller floor plates,” said George Tikijian, a multifamily property broker with the Indianapolis office of Chicago-based Cushman & Wakefield. “This is by far the newest office building being converted.”

Other structures, including the King Cole building just south of Monument Circle and the Stockyards Bank property along East Market Street, are also undergoing conversions, but those are to hotels, as Keystone is doing at the Illinois Building. Those projects—while themselves complex—generally require less new mechanical infrastructure.

Keystone said it’s paused its InterContinental project. Pavlik told IBJ the firm completed two model rooms before the pandemic but is waiting for the hotel industry to recover before deciding how to move forward.

“We have ordered a new market study and, if the projection looks good, we will be ready to restart construction,” she said. The project is expected to take 14 months once construction resumes.

Andrew Urban, a capital-markets broker with the Indianapolis office of Toronto-based Colliers International, said Indianapolis is still catching up to other metropolitan areas, both with its addition of multifamily units to the city core and with its conversion of underperforming office space.

He said in other cities, developers often add residential and retail to underused office buildings.

“There’s a large precedent in other major markets like Chicago and New York, for buildings with true mixed-use roles,” Urban said. “And if you think about it, it isn’t really much different than, let’s say, Bottleworks, where you have some office buildings, a hotel, retail, movie theater, apartments that are planned on-site, all within the same campus where people kind of mix and mingle.”

He said several office-building conversions could be coming down the pike in Indianapolis—though whether the new uses will be apartments and condos or hotels, or a mix of the two, he’s not certain.

“That trend is continuing because of demand on the capital markets for stabilized multifamily assets—there’s still an incentive there for developers to do that versus office assets,” he said. “Naturally, they’re just following where the money is.”

Tikijian agreed, adding that most downtown multifamily properties have fully recovered from the pandemic. He said many people in their mid-20s who haven’t started families are still making the move downtown—and that age bracket is driving most of the leasing post-COVID.

“The demand is still strong,” he said. “The market is largely recovered, and properties are doing well, but there’s not that many new units being delivered. So, the supply is down quite a bit.”

In fact, 220 North Meridian and a project at 421 N. Pennsylvania St., known as Industry Indy, are the only two residential projects in the city’s central business district expected to be completed by the end of the year.

But there will likely be office buildings available to redevelop. Bloomberg reports the United States is facing a $1.1 trillion office-space obsolescence problem. Accounting for about 30% of the total market, some office buildings have lost much of their value and are being given up by users because they don’t meet post-pandemic needs.

That could create a major glut in downtown market, Urban said.

According to a report from the local office of Cushman & Wakefield issued for the fourth quarter of 2021, the downtown office vacancy rate was 18.7%, compared to 14% for the same period in 2019.

A blueprint?

At least one property being eyed for full residential or a mix of office and residential down the road is the City-County Building. The city is continuing to evaluate its own long-term real estate needs but recently released a request for information soliciting responses from developers about converting the building to apartments with a potential office component.

The 220 Meridian project could offer somewhat of a road map.

“Keystone, to their credit, is being a little bit of a leader here,” Urban said. “In a lot of ways, it does show the path—or what would be required—for somebody to do the same at the City-County Building. Obviously, buildings are different, there’s that nuance, but I do think it does give some precedent for others to see how Keystone is approaching this.”

Tomyn said that even Keystone is likely to take a different tack if it does another office conversion down the road.

“Even though we may very well convert another office building, it won’t be the same—simply due to the nature of the infrastructure, the building itself and such,” he said.

“I think [conversions are] a viable model. The key is buying under replacement cost and having a vision for it—the vision is a big part of it.”

Keystone’s Pavlik said that, given the firm’s approach to risk-taking, it’s likely one of the few local firms that could do a project like 220 Meridian.

“I think in a lot of ways we’re pioneers,” she said. “We’re willing to take risks to make something greater than other people can envision.”•